Tony Perez a key part of Black History

Tony Perez helped open doors for fellow Afro Latinos

As a teen in Cuba in the 1950s, Atanacio Perez dreamed of being the next Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso. While many African American kids aspired to be like Jackie Robinson, Perez had another idol.

The Cincinnati Reds legend who made his name as Tony Perez longed to follow Miñoso’s trail out of their island. Miñoso became the first Afro Latino in MLB history in 1949 with the Cleveland Indians. Two years later, Miñoso was an All-Star with the Chicago White Sox and the runner-up for the American League Rookie of the Year award.

“When I was growing up, Minnie Miñoso was the big name in Cuba, the best player in Cuba when he played for the White Sox,” Perez said. “Everybody wanted to be like Minnie. I used to tell my parents, I’m going to be like Minnie Miñoso. They always said, ‘Don’t dream that high. You will never be like Miñoso.’”

Much like Robinson with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Larry Doby with the Indians, Miñoso is one of the most important sports figures in Black History. They opened Major League Baseball for players of African descent, whether African Americans or Afro Latinos.

Faces of Major League Baseball

Because of those men, Blacks are among the biggest names in MLB today. Heck, in many cities Blacks are the faces of their MLB teams. Slugger Vladimir Guerrero Jr., the 2021 All-Star Game MVP, is the biggest name in Toronto.

Fernando Tatis Jr. is more than the face of the San Diego Padres. He’s the face of San Diego sports and perhaps even all of MLB. The reigning AL Rookie of the Year (Randy Arozarena) and AL batting champ (Yuli Gurriel) are Black too.

Tony Oliva and Minnie Miñoso finally land in Cooperstown

2021, the Year of the Cuban in Sports

Negro Leagues’ Elevation Improves Minnie Miñoso’s Hall Resume

Those are just a few of the stars who are benefiting from the barriers Tony Perez, Roberto Clemente, Felipe Alou and many other Afro Latinos broke while marching through the Jim Crow South on their way to prominence.

They endured quietly and even lost parts of their identities while dealing with racism in the minor leagues and throughout their brilliant careers. In Alou’s case, he even dealt with racist treatment from the media in two millenniums late into his brilliant managing career.

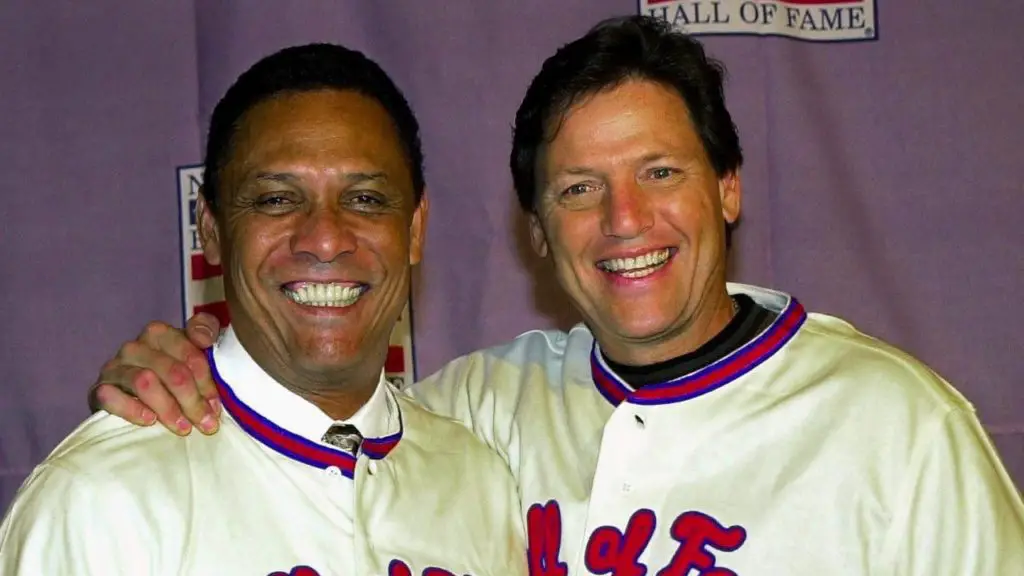

Tony Perez has company in Cooperstown

Miñoso opened the doors for Hall of Famers Atanacio “Tani” Perez, Roberto Clemente, Juan Marichal, Orlando Cepeda, Pedro Martinez, Vladimir Guerrero, Sr., Tony Oliva and David Ortiz.

This July alone, there will be three Afro Latinos inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Miñoso, Oliva and Ortiz.

Seventy-three years after Miñoso’s debut with Cleveland, he’ll be inducted posthumously in July. Oliva, who also considered Miñoso his idol growing up in Cuba, will join him in the Class of 2022. He’ll be joined by Boston Red Sox great David Ortiz, a native of the Dominican Republic whose jovial personality mirrors Miñoso’s demeanor in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

As we celebrate Black History Month, it’s important to remember the sacrifices of Afro Latinos in America.

Perez lost part of his identity as he chased his big league dreams. His parents named him Atanasio and affectionately referred to him as Tani.

From Tani to Tony Perez

The native of Camaguey, Cuba, signed with the Reds as an international free agent. He began his professional career in Upstate New York with the Geneva Redlegs. He first had to go to spring training in Tampa, Fla.

“I was Tani all my life growing up,” he says. “When I was a kid everybody in my hometown knew who I was, like Tani. When I came in 1960, I came to spring training in Tampa, Fla. They started calling me Tony. I didn’t have English (skills) to say, ‘No, no, no, wait a minute. I don’t like that.’ …

“They called me Tony, and I had to take it because I didn’t know how to say no. I didn’t want to say no to anybody. Even one (person) told me that Tani didn’t look like a ballplayer’s name. They said Tani was a woman’s name, a girl. You know, Tani? ‘Tony’s more like a man, like a player,’ somebody told me that. I didn’t like it, but I didn’t say anything.”

That first spring training also gave Perez, 79, his first taste of Jim Crow laws. He couldn’t stay with his teammates on the white side of town. Tracks literally divided the Black and White section.

Latin American, Afro Latinos and Blacks literally stayed on the “other” side of the tracks from their teammates.

Dealing with Jim Crow

Life was a little better when he played in Geneva in 1960 and 1961. That all changed in 1962 when he played in Rocky Mount, N.C., with the Class B Leafs. Life wasn’t much better off the field in 1963 when Tony Perez played in the heart of the South in Georgia with the Macon Peaches in 1963.

There was no escaping the Jim Crow laws. Unlike Cuba, Afro Latinos couldn’t eat with their white brethren in the South. There was no escaping the separate public bathrooms and drinking fountains for Blacks and whites.

On long trips through the South, Perez and his Afro Latino and African American teammates couldn’t eat inside restaurants with their teammates. They had to pick up their meals at a side window if they were even allowed to get off the bus. Often, they had to stay on the team bus and wait for a teammate to bring them their food.

“I used to have to wait in the bus because I couldn’t go down to eat with the rest of the team,” Perez said. “Then I had to wait until somebody, some of the players, (brought) me some food. That happened to me too. A lot of places in downtown when I played in Rocky Mount or Macon I could not go eat. I had to wait.”

Big Red Machine

Twelve years later, Perez was one of the heroes of the 1975 World Series and a leader on the Reds’ Big Red Machine. The man who couldn’t speak English well enough to fight for his name now has a son, Eduardo Perez, who is one of the most important voices on ESPN’s baseball coverage.

Perez and his wife Pituka made education a priority at home. They made Spanish important at home while Eduardo and his brother focused on English at school.

By the time Eduardo was a teenager and college player, Pituka Perez made sure nobody anglicized his name. Eduardo loves to tell the story of the time his mom berated him in the dugout in college after hearing the public address announcer introduce him as Eddie Perez.

Eduardo, not Eddie

“She said, ‘I named you Eduardo and I want them to call you Eduardo,’” Tony Perez remembers with a chuckle. “In high school and college, the kids said Eddie. When she heard that, she didn’t like that. She got hot. She told the other guys to call him Eduardo, because that’s what his name.”

Tony Perez never went to school to learn English. He taught himself the language by communicating with teammates and watching English television shows.

He communicated well enough to be considered a team leader on a Reds dynasty that included Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Johnny Bench. Perez also had two stints as a manager in MLB, one with the Reds and another with the Florida Marlins.

He and Pituka raised a proud family willing to speak up for fellow Latinos. His story deserves to be celebrated beyond Cincinnati and the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. He is a hero of the Civil Rights struggle even if he doesn’t see himself that way.

Because of men such as Tony Perez, Black men are among the biggest stars in baseball right now. Who would have thought in 1960 that by 2022 three Afro Latinos would be elected to join Perez, Clemente and Ted Williams in Cooperstown?

Like Miñoso, Tony Perez is a trailblazer

Tony Perez’s beloved mom Tita would tell a young Tani not to say he would be like Minnie Miñoso.

“They always said, ‘Don’t dream that high. You will never be like Miñoso,’” Tony Perez said. “When I got to the Hall of Fame, I said … ‘Tita, I’m here. Remember I told you … I’m going to be a good player. I’m going to be like Minnie Miñoso. That was great.’”

Miñoso opened the door for Perez, and the Reds legend is proud to have helped open many doors for other Latinos and Afro Latinos. On Black History Month and every month, we must celebrate the sacrifices Atanacio Perez’s generation of Afro Latinos made for all of us.

Stay in the Loop

Get the Our Esquina Email Newsletter

By submitting your email, you are agreeing to receive additional communications and exclusive content from Our Esquina. You can unsubscribe at any time.