‘Cuban Missile’ Zach Calzada Embodies American Dream

Texas A&M quarterback Zach Calzada set for first start

Zach Calzada’s personal route to the starting quarterback job at Texas A&M stretches across the length and breadth of SEC country, but the Calzada family’s story begins in Cuba amid the tumultuous takeover of the island by the communist regime of Fidel Castro in the late 1950s.

Zach’s journey to his first college start for the No. 5-ranked Aggies against New Mexico on Saturday night, a week after coming off the bench to pace the Aggies to a nail-biting 10-7 win over Colorado, shows the same determination and ingenuity exhibited by his grandparents, Hector and Maria Del Carmen Calzada, who fled Cuba 60 years ago in search of a better life.

The family odyssey has stretched from Panama to Florida, Missouri and Georgia and now, for Zach and his sister Carolyn, who has committed to play soccer for the Aggies, to College Station.

Time to flee

Grandfather Hector Calzada Sr. knew it was time to leave Cuba after the Castro regime stripped his U.S.-educated father Agustin of his three pharmacies and most of the family’s wealth. He tried to apply for an exit visa but was greeted outside the U.S. embassy by two lines of applicants, each of which stretched four blocks outside the embassy.

Unable to arrange a direct route to the United States, Hector Calzada Sr. and his wife left Cuba on Oct. 25, 1960, for Panama, under the guise of a delayed honeymoon. They settled in Panama for six months and then departed for the U.S. with little but the clothes on their back.

Hector was 30 years old. Maria, a registered nurse, was 28.

Leaving with ‘nothing’

“I had nothing,” Hector Calzada Sr. said. “They took it all away. They didn’t let me take anything. They took all the money in my bank account when I said I was leaving. It was very difficult, very difficult.”

Maria worked as a nurse, but the college-educated Hector Sr. could only find menial jobs. One benefactor, an American family living in the Canal Zone, helped the family survive until they could arrange passage from Panama to Miami in April 1961.

At that time, the U.S. government was dispersing Cuban refugees to St. Louis and Atlanta. With the help and sponsorship of Webster Groves Christian Church, the Calzadas settled in St. Louis in 1962.

Sign up for Our Esquina’s free newsletter.

Hector Sr. took as many jobs as he could during the family’s six years in St. Louis. He assembled furniture. His main job was at JA Weaver, which manufactured pole and line hardware, in the shipping and receiving department.

He became the office manager’s assistant while also working in the afternoons and weekends as a bartender at Chase Park Plaza hotel.

“The people who attended Webster Grove Christian Church were buenisimos, buenisimos (very good, very good),” he said. “They helped us a lot. They got me a job. That’s tremendous.

“This country is tremendous. It gave me the opportunity, my wife and me, to redo our life. It’s been a tremendous success.”

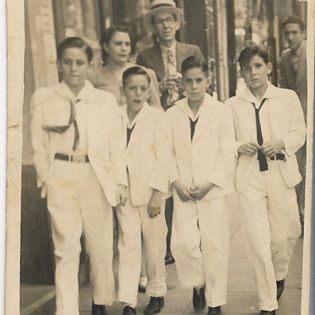

Zach Calzada’s great grandparents followed

Hector Sr. sent for his parents soon after settling in St. Louis. He also tried to bring his three brothers and their spouses to the United States. Only two accepted. Eldest brother Agustin, who worked for the Castro regime as one of the voices of the government’s radio network, refused to leave Cuba.

Hector is the only one of the four Calzada brothers remaining. One died in Chicago. Another died in Atlanta, and the oldest died in Cuba without ever speaking to his brother again.

“I never once saw him again,” Hector Sr. said of his brother Agustin. “I mailed him letters many times, and he never replied. It’s very sad because it doesn’t matter his thinking and ideas because he was my brother.”

Fidel Castro died in November 2016, but many exiles and recent defectors still lament their inability to see family and loved ones left in Cuba.

Hector Sr. noticed the recent protests in Cuba against the communist government. He saw how All-Star Yankees closer Aroldis Chapman, boxing champ Yordeni Ugas and several other Cuban baseball stars have spoken in favor of the protesters.

Many Cuban sports stars in America have embraced the “Patria y Vida” movement and song, which is a counter to Castro’s old “Patria o Muerte” (Homeland or death).

“That was a very big disaster,” Hector Sr. says of Castro’s government. “Let me tell you, before Fidel took over Cuba in 1959, Cuba was known as the sugar factory to the world. Then that changed and they needed to import sugar. That’s communism, señor.”

Zach Calzada makes abuelo proud

From that somber topic, Hector Sr. turned his attention to a happier subject: his grandson, the first Latino starting quarterback in the rich history of Texas A&M football.

“Let me tell you something, Zachary is a wonderful boy,” Hector Sr. says. “I’m very proud of him. Not because of football, but outside of football he’s a very, very fine boy.”’

Fittingly for the grandson of baseball-loving Cubanos, Zach Calzada, who was an Under Armor All-American at Lanier High School in Atlanta before signing with the Aggies in 2019, is known for his arm strength. Younger sister Carolyn has played with the youth national team.

Their mom, Colleen, is an Irish Catholic who graduated from the University of Miami and has embraced Cuban culture.

“She makes the best cafecito,” Zach’s father Hector Jr., known as Tico, says of Colleen Calzada.

“Cafecito” is delicious Cuban coffee.

Tico Calzada was an accomplished swimmer at Tulane University. As a child, he set Georgia swimming records in the backstroke. He realized he wanted to be an elite swimmer at a meet in St. Croix when he was 15.

Years later, Tico found out that his father took out a credit card to pay for him to attend that meet. It took five years to pay that credit card. By then, Hector Sr. was already working in public relations at TRW in Atlanta.

Zach Calzada isn’t family’s only athletic star

Tico eventually became a Division I All-America honorable mention swimmer at Tulane. His younger brother played collegiate soccer, and a first cousin played college baseball. Colleen and Hector both had lower-level scholarship offers to play soccer in college, too.

“We paid attention to where their passions were,” Tico says of Zach and Carolyn. “And we helped to feed that passion.”

Tico said he was following the example set by his parents. Most college swimming scholarships are partial rides only, so Hector Sr. worked during the day at TRW and at Sears on nights and weekends to help Tico pay for his tuition at Tulane.

“I always wanted to give them responsibility so they know it doesn’t matter the type of work you do,” Hector Sr. says. “We taught them that no matter what work they did, they should do the best they could and put the best effort in anything they want to do.

“That has been a great success. I feel very, very proud of my son and my grandson.”

Tico appreciates his parents’ sacrifices. He learned from them and tried to emulate their support with his children.

Hector Jr. followed his parents’ example and is now a managing director at Deloitte. Tico is a devoted father who has given his children the tools to blossom on the field and in the classroom. He has passed on his work ethic and drive.

‘Cuban Missile’

Zach Calzada, who has been nicknamed the Cuban Missile since he was in middle school, is a product of his grandparents’ many sacrifices. The work Hector Sr. and Maria Del Carmen Calzada put in to settle in America has paid off with their children and grandchildren.

“I think that there’s a softening where their soul melts to talk about it,” Tico Calzada says of his parents. “Even my mother in her dementia goes back to her days in Cuba wishing she was there. I think it’s nothing more than where they were so comfortable. This was their home.”

Two generations later, in the heart of Texas, Zach Calzada’s story represents a triumph of the American dream and another expansion of the famous Aggie spirit.

Stay in the Loop

Get the Our Esquina Email Newsletter

By submitting your email, you are agreeing to receive additional communications and exclusive content from Our Esquina. You can unsubscribe at any time.