Chalino podcast shows why fallen star’s narco corridos resonate

Author Erick Galindo proud to tell 'our' stories

It’s been 30 years since Chalino was murdered in Sinaloa.

“Who’s Chalino?”

Wait, you don’t know? Where have you been? He’s only one of the most popular Mexican singers of recent vintage. He was the late narcocorrido singer Rosalino Sánchez Félix, known professionally as Chalino Sánchez.

You don’t even need to say the last name. Chalino is on a one-name basis with the Mexican public like the recently departed Vicente Fernandez, also known as Vicente or even the more diminutive, ‘Chente. You say Chalino and Mexicans and Mexican Americans with any semblance of a cultural connection know his story.

Chalino elicits a wide range of emotions from a fanbase made up mostly of people of Mexican descent. He is iconic in a different way. Chalino’s music was outlaw music. It was often ignored by conservative radio stations because the songs lionized mostly male underworld figures such as kingpins, drug smugglers and assassins.

Vicente Fernandez anchored us to our roots

Marcio Jose Sanchez and Julio Cortez add Pulitzer to triumphant journeys

Julio Cortez Captures History With Latino Flair

These figures were not a comic book creation or mythology as the result of a really good peda. They were real figures. Despite emerging from modest – if not the most meager beginnings – they were portrayed as exceptional in business, great friends, excellent with women and ruthless to enemies.

Fearless Chalino

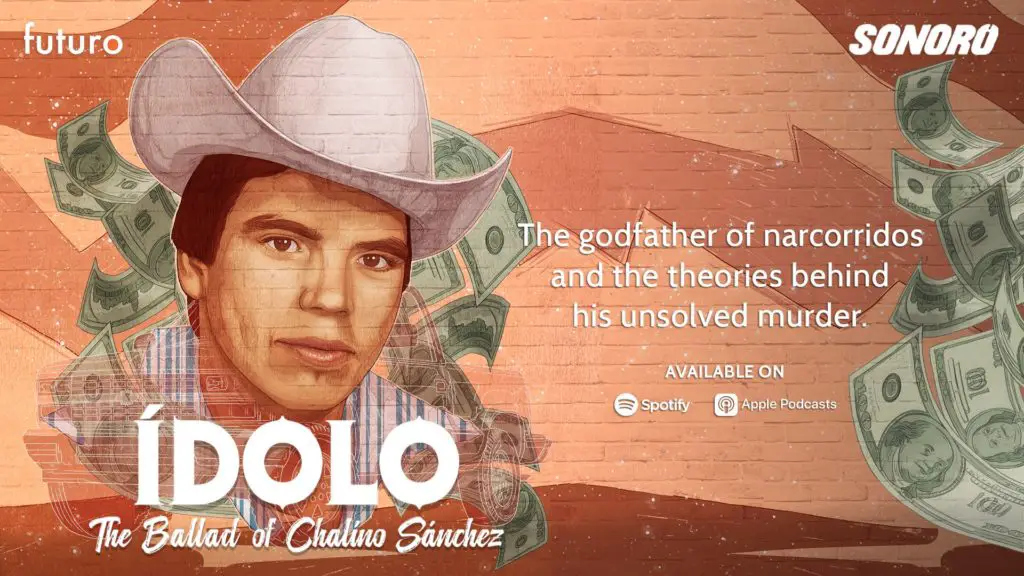

Erick Galindo examines Chalino’s life in “Ídolo: The Ballad of Chalino Sánchez,” a recently released podcast. The bilingual eight-episode series examines Chalino’s life, the chismes surrounding his life and death as well as the motivation behind his 1992 slaying and his enduring legacy.

Galindo, like the name of his production company, does it “Sin Miedo” or without fear. The podcast can be found on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

Galindo, an award-winning and uber talented writer, producer and journalist, is the ideal person to head up this lofty and challenging project. He’s got the spirit, energy and motivation. More importantly, he has the knowledge.

Galindo is a native of Southeast Los Angeles. His family roots are in the northern Mexican state of Sinaloa. Also, they were homeboys. Both lived in Southeast Los Angeles from the area bordering Paramount and Compton.

Los Angeles is a big part of the Chalino story. It’s where Chalino migrated after having to flee after exacting revenge necessary to uphold the family name. Sure, Chalino is Sinaloa, but he’s also Los Angeles.

After all, that’s where he recorded his music. His widow still lives in the family home. Chalino’s story is a Los Angeles one, and Galindo is Los Angeles. He’s well-qualified to represent Southeast Los Angeles, to borrow and paraphrase another late Southland musician, Bradley Nowell of Sublime.

Longtime Chalino connection

Galindo and his brother were Chalino fanboys. Chalino lived down the street from the Galindos. While not known by most English-speaking media, Chalino was “’hood famous.”

Sanchez frequently played at parties and some of the more popular clubs in the area. He was “the most famous Mexican I know,” Galindo said.

Galindo and his brother went so far as to be “rancho chic.” They dressed like “little Chalino clones wearing silk shirts and boots” purchased at the local swap meets where Chalino first sold his self-produced cassettes. Those swap meets cater to a primarily Latino clientele.

“Mom liked his music and would dance to it, but didn’t like the violence,” Galindo said. “But us liking him was probably a relief to my parents because we were kids that were embracing Mexican culture – as we were listening to a lot of hip-hop at the time.”

Chalino is a product of a time and place, of the emerging drug scene in Sinaloa from the late 1970s to the early 1990s and with it the associated violence. Los Angeles became one of the largest receiving areas for Sinaloaenses.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s Los Angeles, especially Southeast L.A., was an exceptionally violent place for Galindo and other Mexican and urban youth.

Success story

Sanchez’s appeal to urban youth was due in part to Horatio Alger-like stories of emerging from nothing to make himself something, which is so common and popular in the United States.

“At the most basic, Chalino is a guy that got out of the ‘hood that made a name for himself,” Galindo says. “He broke out of a scary destiny and in that way, he represented hope to me.”

Speaking from experience, to get out of the ‘hood and make something of one’s self is a collective inner-city obsession. It’s up to you on how you do it. It’s a demonstration of having the right mix of smarts, guts and guile.

The Mexican twist is to make it, but also to have the credibility to have the enduring admiration of the people who are still in the ‘hood. There are many mortal sins, but the most mortal Mexican sin is to forget origins as “el hijo del Pueblo.”

Sanchez embodied that. He demonstrated composure and courage. A frequently shared video on “Mexican social media” shows Chalino reading a note threatening his life. After demonstrating just the slightest discomfort, he proceeds to sing one of his hits, “Alma Enamorada.”

The first time you watch this, it’s shocking. I’ve watched it at least a 100 times, or more. It’s haunting. But that’s why people like Chalino.

He possessed those characteristics that we believe ourselves to have. Unfortunately, he demonstrates the macho bullshit and the bravado that we sometimes, especially urban youth, possess.

In the year he died, he survived a gun battle with a concertgoer at a concert in Coachella, Calif. Violence was the central and enduring theme of his life.

Self made Chalino

Chalino created his own thing and had a knack for survival. Sanchez didn’t use a focus group. His fame wasn’t a studio creation. He fashioned a life for himself in music first by accident. Chalino endured a Tijuana prison stretch by writing lyrics for other inmates and later singing even though his voice was not classically trained.

Sanchez’s voice was nasally and imperfect. He took nothing and made it something flawed yet beautiful.

But again, that’s why we like him. He’s like Mexicans. This is imperfect and it’s hard, but we are going to make it work. WE HAVE NO OTHER CHOICE.

Galindo acknowledges the issues associated with the violence and trafficking themes in Chalino’s music and why that makes it difficult for some to wrap their arms around Chalino and his music.

“One of the concerns is that when you bring up the narco lyrics, that you are glorifying violence or perpetuating stereotypes,” Galindo says.

Yet, we can’t rewrite history. Nor can we eliminate the way violence has been or is a part of our realities. This isn’t a reason to not tell our stories.

“We don’t get to tell stories of people in our community,” he says, referring to the Sopranos writer and producer “David Chase gets to tell stories about his community.”

Mexican community’s story

Galindo views Chalino’s story as a community story. “This could have easily been any one of us,” he says. “Trying to ‘level up’ and get to a better place. He was trying to and fell victim to violence that curses our community.”

Galindo is a storyteller telling stories about a “storyteller” like Chalino. He gravitated to the storytelling, even if they were narco and ‘hood.

“We finally get to be the protagonist of our own stories,” he says. “And at least they aren’t parodies.”

Furthermore, Sanchez is hardly the only singer with ties to the underworld. Galindo is the author of a 2012 book on Frank Sinatra.

“People don’t think of Frank Sinatra like he was connected, but he was in Cuba with Lucky Luciano,” Galindo says. “The only difference was that Frank Sinatra didn’t have a gun on stage.”

As Galindo gets older he can still admire Chalino’s music and still deplore the violence.

“I can hold onto parts I still love but can get rid of the toxic Macho bullshit that can get you killed,” he says.

The Future of Latino Storytelling

Galindo expressed pleasant surprise that this project was “greenlit” to use the parlance of the industry. When asked about his feelings after the finishing touches were put on this project, a relieved Galindo uttered “God damn this worked.”

Galiindo has more stories for us, but it was not until working as a college journalist that he began to understand the power of storytelling and bigger ideas and the uniqueness of his experience.

“I lived in a bubble,” he says. “I assumed Chalino was huge. But I didn’t understand non-Mexicans not knowing who he was. I was blowing people away with Chalino stories.”

Galindo’s ambitious podcast project has been years in the making. According to Galindo, he’s been pitching projects involving Chalino for the last 10 years.

Our stories deserve to be told. Prior to developing this podcast, a Latino- themed project was formulaic to Galindo.

“I would have to start with the dawn of civilization to tell stories and then bring out stats like an accountant about what we consume,” he says. “That’s changing. It’s starting to get easier.”

More Latino stories worth telling

It’s not just the narco story, but there are many other stories worth telling, in the community.

In contrast to Galindo’s Chalino narco story, the talented writer’s looking forward to developing a show titled “Mexican Beverly Hills” for CBS.

The “Mexican Beverly Hills” is a common- Mexican Los Angeles moniker to refer to the suburb of Downey, where many of the residents are Mexicans who like characters from another CBS-show, George and Weezy Jefferson, “moved on up.”

He says the series is a “story of affluent Latinos navigating culture and money when they aren’t supposed to have money.

“I don’t speak for my community, but I want to tell their story,” he says. “We need to tell stories from all walks of life. Latinidad is so diverse and strong and our stories need to be told.

“We need an onslaught of stories that tell human stories of Latino Diaspora. Our time is coming. We’re not there yet. But we’re getting there very soon.”

Stay in the Loop

Get the Our Esquina Email Newsletter

By submitting your email, you are agreeing to receive additional communications and exclusive content from Our Esquina. You can unsubscribe at any time.